Mauricio Rocha: to be Unnoticed, You Need to be Brave

To tell the story of the Anahuacalli Museum and its recent expansion I need to take you back to the 1940s.

The City of the Arts

Muralist Diego Rivera and iconic painter Frida Kahlo had moved their volatile relationship to Mexico City.

They'd packed their suitcases with utopian dreams, such as a unifying City of the Arts built on basaltic badlands.

Rivera dreamed that this City of the Arts would function like a community center and provide a contemporary platform to showcase his massive collection of pre-Hispanic artwork.

Plans were initially designed by Rivera and his friend, architect Juan O'Gorman (a student of Le Corbusier) in the 1950's.

Not completed at the time of Rivera's death in 1957, the building finally became a museum in 1964 with help from O'Gorman and Rivera's architect daughter Ruth.

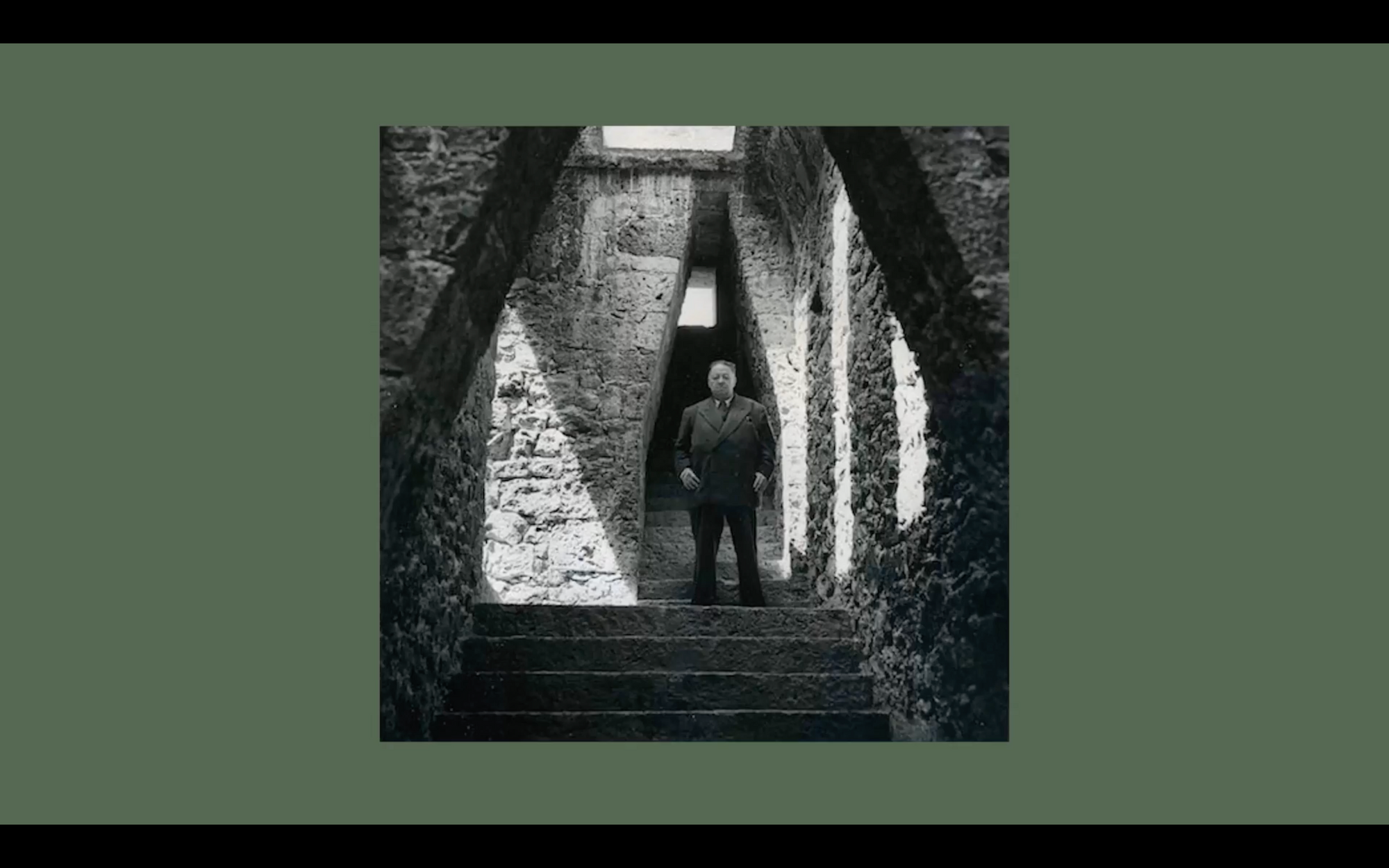

The result? A modern interpretation of a pre-Hispanic pyramid. Built from volcanic rock, the exterior looms large, like an imposing fortress.

'Anahuacalli' is derived from an Aztec word meaning 'house surrounded by water.' Today, the museum calls thousands of visitors to explore the space's rich artistic and cultural history.

Back to the Future

For a long time, the Museum consisted of the main building, two smaller structures and a large public plaza. Any dreams of expansion were abandoned, until very recently.

A competition won by influential Mexican architect Mauricio Rocha was completed in 2021. Rocha is well known for his projects in Mexico City such as the “Center for the Blind and Visually Impaired” and the “House for Abandoned Children”.

The competition challenged the distinguished modern architect to step forward with an idea to help Rivera realise his dream from long ago - an intimidating prospect.

But Rocha found a humble approach made the most sense:

"Designing something silent, quiet... seems to me the biggest risk, which is being unnoticed.

But to be unnoticed, you need to be brave."

The Old and the New Mexico

Rocha's design provides additional exhibition space in the form of three discrete pavilions that hover respectfully over the terrain and don't attempt to rival the scale of Diego's main structure.

An interactive courtyard and walkway connect these modern pavilions to the original Museum while making the most of the ecological reserve.

"Try to make architecture become a connector, instead of an aggressor," suggests Rocha.

"An architecture encouraging you to dive in, as if you were snorkelling in the sea, watching fishes, but here you dive in to watch insects, butterflies, plants."

Rocha has successfully created an inviting public space for visitors to spend time connecting with nature while absorbing gracefully expressed connections between the old and the new Mexico.

In our upcoming series MEXITY, Rocha gives an exclusive interview discussing his approach to the Anahuacalli expansion, his subtle contribution to the architectural dialogue around modernism and why materiality was so important to the success of the expansion.

Join our mailing list of over 22,000 architecture lovers!

Related Viewing on Shelter

Architecture on the Edge | Do More With Less | Casa Cosmos | Eco Friendly House | Infinite Space | BugsBrasilia | David Chipperfield Form Matters | Growing Cities