Sight, Light & Cadence: Rediscovering Arthur Erickson’s Hidden Masterpiece, The Dyde House

Nestled in the quiet aspen parkland outside Edmonton, Canada, the Dyde House stands as a nearly forgotten piece of Canadian architectural history. This hidden gem—designed by a young and relatively inexperienced Arthur Erickson in 1959—is an embodiment of experimentation, innovation, and the spirit of modernism. Thanks to the vision of patrons Henry Alexander Dyde and his wife Dorothy, Erickson was given the freedom to craft a unique architectural retreat that has, until recently, remained a secret treasure.

The Dydes, known for their progressive approach to art and life, had purchased the remote plot with the idea of creating a sanctuary that harmonized with nature. They envisioned a retreat for reflection and renewal, free from the demands of daily life but also untouched by conventional design. Erickson, with his unorthodox ideas, was the perfect match for this ambition. What emerged from this partnership was a radical departure from the traditional architecture of the time—an intimate, modern space crafted from stacked cinder blocks and defined by sharp, clean lines that blended with the surrounding landscape.

Erickson’s approach to the Dyde House was groundbreaking. At a time when Canadian homes often relied on classic brick or wood construction, Erickson’s minimalist aesthetic was a revelation. His design embraced the natural world as much as the structure itself, creating an early example of indoor-outdoor living that would later become a hallmark of his style. The home was small yet elegant, striking a cadence with its environment that allowed the parkland’s light and shadows to define its spaces, embodying a poetic cadence of sight and light.

The Dydes’ only stipulation for the young architect was that the house remain a secret—a private retreat unsullied by public attention. For five decades, this condition ensured that the Dyde House stayed hidden from view, its influence confined to Erickson’s own developing architectural vocabulary. And indeed, the experience of designing this retreat profoundly impacted Erickson’s work. The Dyde House’s unassuming materials and seamless integration with its environment are qualities that would later find grander expression in Erickson’s iconic projects, such as Simon Fraser University and Vancouver’s Robson Square.

But despite its pioneering design, the Dyde House was virtually forgotten for decades. It wasn’t until 2016, when a group of architects rediscovered it, that Erickson’s early masterpiece came back into the public eye. Though the structure is in need of repair, it remains an eloquent testament to Erickson’s vision and the patronage of the Dydes, rich with the language and philosophy that defined his career.

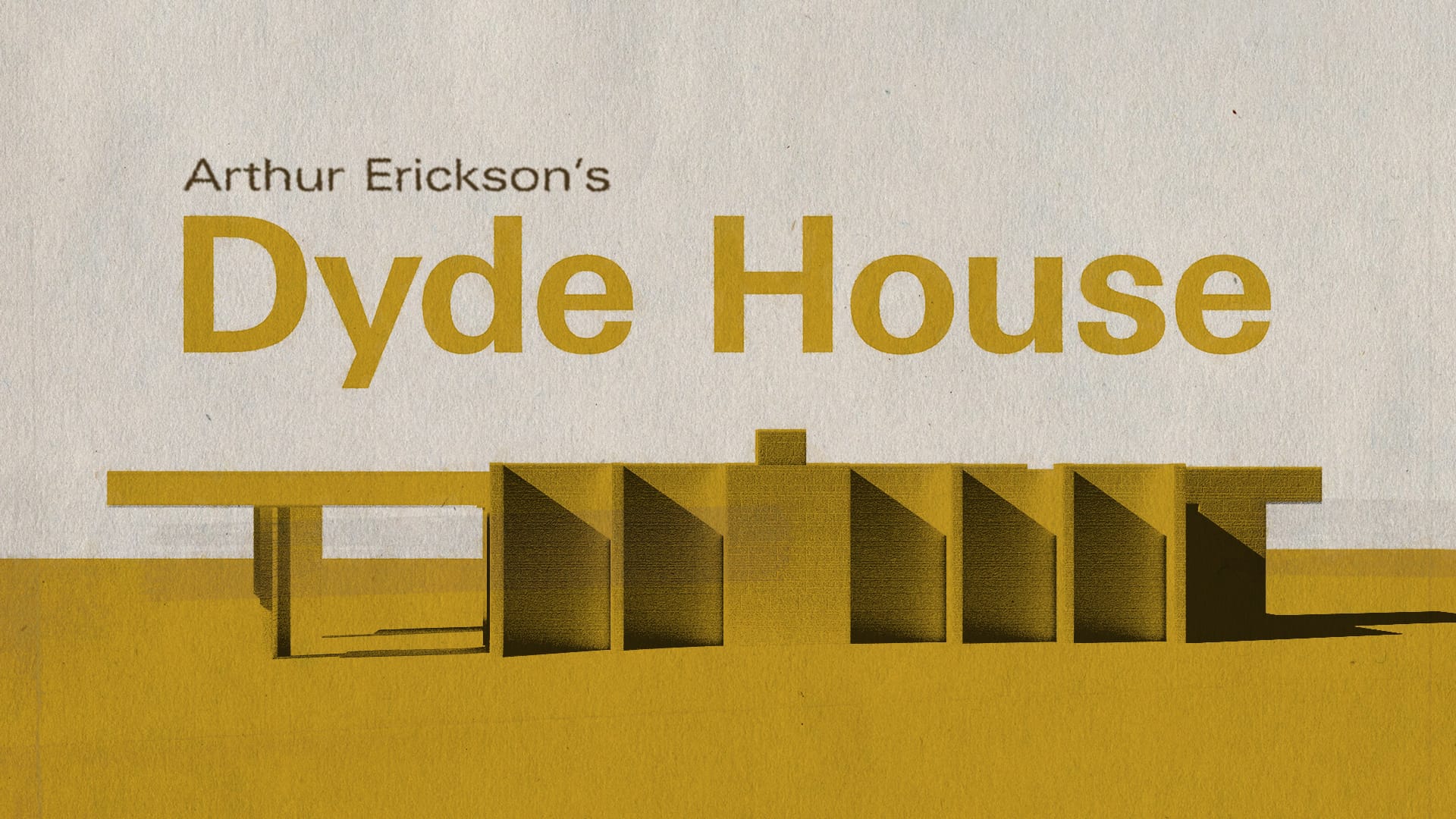

In a recent trailer for Sight, Light & Cadence: Arthur Erickson's Dyde House, viewers catch a glimpse of this elusive work, finally poised to share its quiet brilliance with the world. The film not only chronicles the rediscovery of Dyde House but also reflects on Erickson’s philosophy of design—an architectural language that sought harmony with nature and resonance with the human spirit. As Erickson himself once said, “Great buildings that move the spirit have always been rare. In every case, they are unique, poetic, products of the heart.”

For Erickson, the Dyde House was precisely that—a private, understated space “not to be shown off,” but to be experienced as a retreat into nature. Now, as it emerges from the shadows, Dyde House invites the public to experience the birthplace of Erickson’s vision—a pioneering experiment in modern architecture that continues to inspire, reminding us of the beauty found when architecture and environment speak in unison.

Watch the film now on Shelter